Suspected Concussion Stats from the Ulster Bank League

Referees from the Ulster Bank League were asked to report suspected player concussions from the 2014/15 season via an online form, to be monitored by the IRFU‘s medical department. The union recently sent a memo to referees with some initial results: 26 suspected concussions in 425 games.

Extract from a memo sent by the IRFU to referees about suspected concussions in the 2014/15 Ulster Bank League

The memo had not been released to the media but the IRFU confirmed it. When asked, they also offered some other data on the injury mechanism reported by the referee for each suspected concussion.

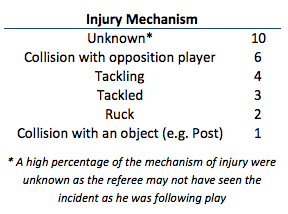

Injury mechanism, as reported by referees, for suspected concussions in the 2014/15 UBL

The 26 concussions suggested a rate of 1.5 concussions per 1000 player hours in the UBL, compared to 10.5/1000 in the Aviva Premiership in the 2013/14 club season. I was curious about that gap; 1.5/1000 and 10.5/1000 seemed a very long way apart for what is ostensibly the same game.

Between 2009 and 2012 researchers looked at the community gamei in England (amateur and semi-professional). Their injury surveillance study found a concussion incidence figure of 1.2/1000 hours. The study was based on injuries that kept a player out for a minimum of eight days, however, which is an important point. We’ll come back to that.

Being merely an ignorant hack, not a doctor, as part of the background to this pieceii I talked to a number of people with considerable knowledge of this field, including Dr. Keith Stokes of the University of Bath. He was part of the team behind the 2009-12 community rugby study. He’s also part of the English Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance Project. It’s good to talk to smart people. You learn stuff.

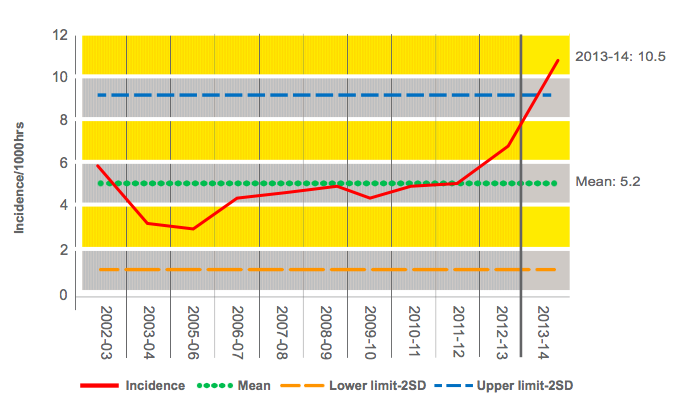

The England Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance Project, in place since 2002, has shown a large increase in the rate of reported concussions in the elite game. That increase has been most visible since the 2011/12 season, as can be seen from the below graph.

Concussions by Premiership players in the 2013/14 club season (source: England Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance 2013/14 Season Report)

A Change in Incentive?

Awareness and educational improvements aside, it should not go unnoticed that 2011/12 also marked a change in concussion protocols. The Graduated Return To Play protocol enabled a team’s medical staff to declare a player fit to return to active playing duty after a minimum of six days. Previously the minimum had been 21 days unless cleared by a neurological specialist.

There is no doubt that the incentive to withhold a concussion diagnosis certainly changed. However, it’s important to stateiii that there has been no causal link proven between the decrease in the minimum stand-down period and the increase in reported concussions. The UBL minimum absence for a concussed player is 21 days; 23 days for age-grade rugby.

Know what’s being counted

There are a number of issues when considering data on concussion incidence. For one thing, one must be sure what’s actually being counted. Roughly one third of concussions by Premiership players in 2013/14 saw the player report no more symptoms and return at the six day minimum. If the community study had used the same eight day threshold at the professional level it would miss those “minimum GRTP” concussions. This is not to knock either method of data collection; it’s just important to check the context.

UBL data: crude, but it’s a start

The UBL data isn’t great. These are referees, not medical professionals. And they were, after all, “suspected” concussions rather that confirmed. And the data was based on refs actually logging the data afterwards which, with the best will in the world, might not always have occurred. In fairness, the IRFU’s Head of Medical Services Dr. Rod McLoughlin said that the stats were crude when we sat down for a chat about them. Not true injury surveillance, he said, rather an early indicator in the absence of data in the amateur game. Also, a way to show clubs that the IRFU are serious about tracking these things.

When the IRFU medical department saw a name pop up on a team sheet before the 21 day minimum they said they followed up with the club. This happened twice. There were two cases where they did follow up. “Like everything, we got a mixed response” said McLoughlin, explaining that while one coach had been delighted to see evidence of the system at work the other coach had been more cautious, perhaps wary at being second-guessed by the union. In each instance the club confirmed that the player had been medically examined and had not been diagnosed with concussion.

Concussion stats in Irish professional rugby, and filling the amateur data gap

McLoughlin has complete access to injury information for the Irish professional game where the four provincial setups, along with the national side, now all use the same Kitman Labs injury recording system. McLoughlin said there had been 42 concussions suffered by Irish professional teams in 2014/15 between Pro12, Champions Cup and test rugby. This equated to 8.5/1000 player hours.

There isn’t the same level of data for the sub-elite level in Ireland. To fill this gap, along with the referee reporting system an injury surveillance study in Ulster schools rugby began last season (the IRFU said initial figures suggest a confirmed concussion rate of 6/1000 hours) and last week the union announced it is seeking an injury surveillance research partner for the Irish amateur game. “We want to partner with an established research body that has the expertise to do the research but that will also produce independent figures” said McLoughlin, who said it would be very much modelled on similar work in England.

“The one thing we know about concussion is it is a changing face all the time” said McLoughlin. “What we have is people, with today’s knowledge, judging on how it was managed ten years ago. That’s probably a little bit unfair on the people of ten years back. What we’re doing today may be laughed at in ten years time or five years time.”

Science is about an accumulation of knowledge, with decisions made based upon the best knowledge of that time. In a decade’s time who knows what we’ll know about brain injury. The point being made was fair, but it assumes rational and honest actors across the board. McLoughlin himself spoke of the pressures one might have felt as an doctor in the All Ireland League years ago: “you had this thing of people would be putting pressure on you to say it was a hamstring or something. That it wasn’t a concussion.”

We’ve heard this referred to before. The ABC of head injury diagnosis: Anything But Concussion.

It was interesting to note in our chat that the IRFU does not yet have plans to supply data from the professional game (i.e. via the Kitman Labs system in use by all provinces and the national side) for independent research. One hopes that, even from the perspective of “optics”, they might add this to their concussion research roadmap.

Recorded concussion stats in the amateur game will rise, and that’s ok.

When we see the stats from the 2015/16 UBL season the reported concussion rate should almost certainly rise. This will likely be via a combination of factors, including greater awareness by players and coaches. Referees too, who perhaps did not fully engage with the system in 2014/15 or perhaps (innocently, due to misunderstanding) reported suspected concussions only where the referee had insisted upon a player being removed from the fieldiv. Hopefully the data will be shared, and will be useful.

Keith Stokes, speaking about the English community game, put it thusly: “I would imagine they would increase, in terms of reporting. I would think that, almost certainly there are concussions that aren’t recognised at the community level. Almost certainly. Because even when there were really good medical support staff at professional clubs, prior to there being this surge of awareness and interest, there were still concussions not being recognised and not being reported at that time. Partly because people weren’t aware of how serious this could potentially be, and so therefore it wasn’t a big thing, and partly because players weren’t reporting it, but also partly because we weren’t looking for it.”

Well we’re looking for it now. Perhaps too much, sometimes. A player gets a knock to the head and all cry “concussion!”. A player passes a Head Injury Assessment and returns to the pitch; people get confused when he might subsequently be diagnosed with concussion. They get angry. The system must be broken.

Well, no. The HIA is a test. Complex yet also crude, considering the myriad intricacies of the human brain. The point is that getting people through HIAs gives us some data. Getting concussions recorded and tracked gives us data. And if we do that in the amateur game as well as the professional (not to mention under-age and schoolboy/girl levels) we might learn a bit more about the differences between similar types of human playing what should be a similar game.

The goal: breakthroughs in understanding of a complex neural event via an evidence-based approach.

P.S. At the 2015 Rugby World Cup there will be further safeguards. McLoughlin said any player going through the Return To Play protocols would be subject to examination by an independent doctor. “I want to see that player that you’re saying is fit and ready”, they might say. There will also be an “untoward incident review” should a team be perceived to have not managed a concussion appropriately.

You can read a related column in the Irish Times of Wednesday, September 16th, 2015: http://www.irishtimes.com/sport/rugby/andy-mcgeady-data-on-concussion-will-help-to-protect-rugby-players-1.2352921