Revenge of the Nerds

This article was printed in the Irish Examiner of Saturday, April 20th 2013: http://www.irishexaminer.com/sport/other-sports/revenge-of-the-nerds-228948.html

Why is the size of an NFL quarterback’s hands more vital to some teams than others? What is “The Dwight Effect” and why is it important in the NBA? Why is putting in effort to measure the relative values of Cristiano Ronaldo and Leo Messi not a worthwhile exercise for professional soccer teams?

These were questions posed, discussed and answered at the 2013 Sloan Sports Analytics Conference last month in the enormous Boston Convention Center.

If you think those questions sound a little nerdy, you’d be right.

Dubbed “Dorkapalooza” by ESPN’s Bill Simmons in 2009, the Sloan conference, run by the famed Massachusetts Institute of Technology, began seven years ago as a basketball-centric event held in a few MIT classrooms and attended by 200 people. This year there were 2,700 attendees with 75 panels and presentations covering everything from baseball to soccer to Nascar. Some of the biggest names in US sports media were there, as well as NBA and NFL owners and general managers.

So, Sloan is a very big deal. But what is “sports analytics”, anyway?

Definitions vary, but at the heart of sports analytics is a desire to use data in some fashion to improve understanding about some aspect of sport. From a coach’s point of view this might be to find out which of his players perform better in a particular defensive formation; a team owner might want better information on fan behaviour and purchasing patterns in the stadium; a team doctor might seek insight into specific aspects of player health, especially for those returning from injury.

The methods and motivations might vary but it’s all analytics — gathering data, analysing it in the hope of creating new, valuable information to better inform the decision-making process, either on or off the field.

With the rich basketball analytics history in Sloan’s veins, conference-goers were not surprised to see 29 of the 30 NBA teams in attendance in 2013 (the LA Lakers being the sole holdout). Major League Baseball clubs had healthy numbers in attendance, quite appropriately considering it would be somewhat unlikely an event like this would have reached such a scale were it not for the 2003 book Moneyball, written by Michael Lewis about the Oakland Athletics and their search for undervalued talent.

Where European sports are concerned, Manchester City, Arsenal, Chelsea and Reading all had people at Sloan. There were also two chaps from the English Cricket Board, Pat Howard from Cricket Australia, Bulldogs rugby league analyst Luke Gooden and Rob Carroll, a GAA video analyst from Ireland.

Major stats providers like STATS, Opta, Prozone and Infostrada were there with smaller vendors just trying to get a new sports product in front of some influential eyes.

And then there was a last group, comprising individuals who perhaps more than anyone else have a direct financial interest in understanding more about what goes into making a winning (or losing) team.

These people don’t often speak on the record, work a lot in Las Vegas and possess somewhat different attitudes to sports gambling than most of those working on Capitol Hill. One might call them the “sports investment” community.

The Chief Operating Officer of the NFL’s San Francisco 49ers is a slight, clean-cut man called Paraag Marathe (pronounced PUH-rawg muh-RAH-tay). He’s got an MBA from Stanford and worked for Bain & Company as a management consultant before being hired by the late, legendary 49ers head coach Bill Walsh to work on an algorithm to determine the optimal exchange rate for draft picks in the NFL’s annual draft. That was in 2001; 12 years later, Marathe’s still there.

Speaking on the keynote Revenge of the Nerds panel along with Daryl Morey, Mark Cuban and Nate Silver, Marathe was one of many speakers at the conference to highlight a key challenge for those keen to use analytics in sport: communication.

Many analysts are, like Marathe, not drawn from the ranks of former professional athletes. Having not been in the sacred space that is the locker room, being able to communicate effectively to bridge that gap is absolutely vital. After all, if an analyst cannot communicate a particular concept effectively to a coach then the impact of that piece of analysis, no matter how brilliant it might have been, is effectively worthless.

“A five-out-of-10 piece of analysis is better than a 10-out-of-10 analysis presented in the wrong way”, said Marathe.

Even when the perfect analysis of a situation is available it’s sometimes tough to get everyone on board, as Jack Del Rio, current defensive co-ordinator for the Denver Broncos, explained to a packed Saturday Sloan audience.

Beforehand, on the giant big screen behind the armchairs on which the Monday Morning Quarterback panel sat, the crowd was shown a minute’s worth from a Jacksonville Jaguars-NY Jets game in 2009, with Jaguars running back Maurice Jones-Drew barrelling through the Jets defence only to take a knee at the one yard line with the goal line at his mercy.

After Jones-Drew refused the easy touchdown he was almost universally lauded. “There’s a player who gets it!” cooed the commentators at the time, praising the running back’s unconventional but apparently super-smart play. It had been late in a tight game and scoring immediately would have given the Jets enough time with the ball to perhaps get a score themselves.

But Del Rio, who had been Jacksonville’s head coach at the time, told the audience that in discussions on the sideline before that play Jones-Drew had been about as far from “getting it” as he could have been. As Del Rio tried to convince both his running back and offensive coordinator that refusing the touchdown would be the correct strategic move, the head coach heard his star player insist “But I want to score — I need to take care of my fantasy owners!”.

Former Jets and Kansas City Chiefs head coach Herm Edwards was also on the panel with Del Rio and the former NFL cornerback was clear at how the game had changed: “Twenty years ago you wouldn’t even think of doing that. You’d score the TD then go play defence.”

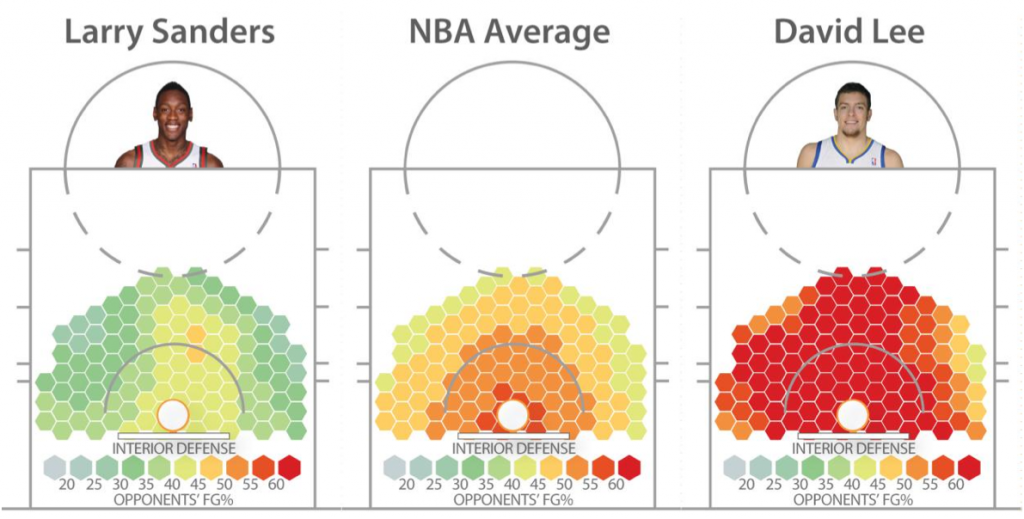

One of the undoubted highlights of the conference was a research paper submitted by Kirk Goldsberry and Eric Weiss of Harvard University. The topic? Interior defence in the NBA, roughly translated as defending the space just beneath and directly around the basket. This tiny piece of hardwood real estate is important because shots taken from there are successful over 50% of the time. As a result, it’s the most vigorously defended space in the professional game.

The paper, given the catchy moniker “The Dwight Effect”, was the result of the work of Goldsberry and Weiss in the field of optically tracked game data, known as XY data, and its potential to revolutionise how team sports are analysed and understood is enormous.

The XY data was collected using a system called SportVu, now installed in 15 NBA arenas. Using technology originally designed in Israel for missile tracking, multiple tiny cameras are installed high up in the roof that optically capture the movements of the players and the ball on the field 25 times per second. This information is all recorded and stored and, importantly, shared between all teams that have installed the system.

Goldsberry, a dapper 6ft college geography professor, combined his love of basketball and spatial analysis to demonstrate how Milwaukee’s Larry Sanders was one of the best interior defenders in the NBA based on how unsuccessful opponents’ shots were when Sanders had been in a defensive position close to the basket. This was impressive stuff, well received by a packed audience. It got better.

Making opponents take bad shots seems like a pretty good thing, but what if one could demonstrate a defender was so good that he actually prevented shots from taking place in the first place?

By measuring the drop in the number of shots taking place when a player was defending that part of the court, Goldsberry and Weiss submitted Dwight Howard of the LA Lakers as the most effective player in the league. It was The Dwight Effect.

This is “big data” and to filter and get value from that sort of data it’s necessary to have people who have serious data analysis skills. Some NBA teams are following baseball’s lead and hiring entire teams of analysts while being ferociously secretive about exactly how large the teams are, never mind the sort of things they look at. This is in surprisingly stark contrast to the NFL’s St Louis Rams who, as admitted by Kevin Demoff, their executive VP of football operations, don’t currently employ a single dedicated analyst.

As the conference has grown over its brief seven-year existence, it’s fair to ask how attendees from pro teams can really benefit from being at Sloan. After all, they’re not likely to share ideas, are they?

Farhan Zaidi, director of baseball operations for MLB’s Oakland A’s, said that he enjoyed attending Sloan because of the “intellectual horsepower” at the event as well as the benefits of cross-pollination, where seeing how ideas and concepts are applied in one sport can sow seeds of new ideas in another.

Baseball and soccer are not similar sports on the surface. But at the Sloan conference of 2013 there emerged a perhaps unlikely connection between them.

Chris Anderson, a behavioural political economist, is the author of The Numbers Game: Why Everything You Know About Football Is Wrong. Responding to a question on Sloan’s Soccer Analytics panel about measuring the relative value of superstars like Ronaldo or Messi, Anderson said something that to many would have seemed rather surprising.

Firstly, the former semi-professional soccer player said that doing such research was a waste of time for professional teams as no club in the world would realistically have the straight choice between buying Ronaldo or Messi at any given time.

Secondly, he said that in terms of improving a team’s results, superstars are overrated. According to Anderson, research has shown the impact of improving the worst player on a soccer team is generally far higher than improving the best.

The Oakland A’s were one of the surprise packages of the 2012 season, finishing top of their American League West division and reaching the play-offs for the first time in seven years despite having been forecasted to be among the league’s worst. As befitting the club about which Moneyball was written, the A’s achieved this without superstars.

“Star players are good — we’ll take ’em”, said Zaidi. But 10 years on from the publishing of Moneyball the A’s are still a low-payroll team in a sport where there is no hard salary cap. “But if we do everything the same as everybody else does we’ll just play to our payroll and that would be a meaningless existence”.

Instead of trying to battle bigger teams with deeper pockets for star players, in 2012 Beane and his Oakland front office specifically concentrated on improving the worst players on their roster. “We even had a term for it in the office — managing the roster from the bottom,” said Zaidi. He was clear that the strategy had come from an in-house study but thought the remarkably similar observation from soccer was interesting, “especially since it’s not particularly intuitive”.

In a team sport, analytics is typically viewed as being about performance measurement, trying to accurately isolate and assess the contribution of events, actions and players towards a combined team effort. But there are more ways to measure than one might think.

Scott Pioli, former NFL executive with the New England Patriots and Kansas City Chiefs, shared one of his great recruitment mistakes when discussing the importance of hand size for an NFL quarterback. Kliff Kingsbury, a sixth round pick by New England in the 2003 draft, had very small hands, the smallest hand size measured at the combine, a showcase for the cream of that year’s college football talent.

In retrospect, explained Pioli, this should have been seen as a very important measure when one considers that the Patriots were drafting someone who would be trying to throw the ball in New England’s regularly inclement winter weather. Current Patriots quarterback (and future Hall of Famer) Tom Brady has enormous hands, said Pioli, which makes a big difference in his ability to control the football in bad weather games.

There were 18 NFL teams represented at Sloan this year. That figure doesn’t quite compare to the NBA’s 29 of 30 teams in attendance but for football fans who want to see their sport run in a smarter way it’s undoubtedly a move in the right direction.

Many big names at the conference had originally made their names in other fields before moving into the sports world. Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban is an entrepreneurial billionaire; Marathe worked in management consulting; Morey, co-chair of the conference and current GM of the NBA’s Houston Rockets, was a computer science major and a strategy consultant.

One of the biggest names at Sloan had taken the opposite journey.

Nate Silver is a skinny chap, with a pale, bespectacled face. Combined with a slightly nervy disposition and manner of speaking it perhaps adds up to his having the look of the nerd about him. And maybe he is.

He’s been an economic consultant and a professional poker player, but where Silver first came to more general attention was when he developed PECOTA, a system for forecasting the future performance of players in Major League Baseball based on historical comparables. Now, of course, Silver is far more widely known as the man behind the New York Times’ FiveThirtyEight blog, forecasting results in the US presidential elections.

To say he has been quite good at election forecasting is to understate the matter somewhat; in the 2008 election Silver correctly forecasted 49 of the 50 states. In the 2012 election he went one better, successfully predicting the results for all 50. Some of these forecasts contrasted wildly with views some political commentators had espoused as late as the election night, most notably on FOX News, with some political talking heads steadfastly refusing to change their beliefs even as the results continued to prove Silver had got it right. “A lot of the press coverage of politics is total bullshit that adds no value to society at all,” said Silver.

The battle between beliefs and facts in politics was certainly a theme of the last presidential election, not least the election night itself. Vested interests of television networks notwithstanding, a similar battle is being fought today in sports featuring an invasion of analysts armed with laptops and spreadsheets and ever-growing databases generated by precisely-calibrated cameras as players run around courts, diamonds and fields like so many dots on a screen.

In terms of how advanced statistics are viewed and accepted in a particular sport is relative to what has gone before. In a stat-heavy sport like baseball, the battle isn’t necessarily between guys who use stats and guys who won’t, it’s really about “old stats”, like Wins, Runs Batted In and Stolen Bases, versus “new stats”, like ERA Plus or WAR (Wins Above Replacement).

It’s broadly similar in the NBA as newer stats emerge offering more insight than the simple counting of shots or assists. Even in the uber-jock world of the NFL where, as Pioli put it, “even the smartest people in football don’t want to be seen as smart”, analytics is making its presence felt, although at a much slower pace.

Rugby and soccer don’t have that same stat-heavy tradition on which to draw so in some ways the battle is very different; instead of old stats versus new it can be about introducing the use of data into the decision-making process for the first time.

Events like Sloan perhaps provide a window into the future of how analytics might change the way sports like soccer, rugby and GAA are played, televised and reported upon in the future.

The nerds are here. And, if Sloan is anything to go by, they are the future.

Photo Credit: SLY Photography

Boy…..you’ve managed to make sport boring. Kudos

Sorry you didn’t enjoy the piece. Thanks for reading.

Great stuff Andy… I enjoyed it and it seems clear as a Rugby fan that stats about to become a big part of the sport.

Thanks for the comment – glad you liked it.